Interview: Vince Kaminski

Market veteran Vince Kaminski discusses the biggest risks to energy firms today and whether risk teams can ever prove their value

Famed for being a whistleblower at Enron in the early 2000s, Vince Kaminski’s pioneering career in the quantitative analysis of energy markets demonstrates intellect and integrity in equal measure.

“People like me don’t usually interact with the board,” Kaminski says in this exclusive interview with Energy Risk. “I suffer from uncontrollable urges to tell the truth!”

Here he shares his thoughts on the most pressing issues affecting energy risk management today and the biggest changes he’s seen over his career.

What are the biggest threats to energy businesses today?

I think geopolitical risk is the biggest short-term risk we face today. This is the most dangerous period of my life, more dangerous than even the Cuban missile crisis of 1962. Back then we had two adversaries with well-defined objectives and established channels of communication. Today, the situation is much more complicated, with many parallel conflicts. The potential for mistakes, miscommunication and overreaction is great.

In the long run, the greatest risks stem from climate change, both physical risk and transition, or policy, risk. Increases in extreme weather events mean company infrastructure is under greater threat of being destroyed through flooding, hurricanes and fires, leading to disruptions to operations. This would increase operating costs and lead to massive balance-sheet write-offs and losses for creditors. Energy firms are also hugely exposed to transition risks from policies designed to stop and reverse global warming, like, for example, carbon taxes, which could result in huge levels of stranded assets.

Both physical and transition risks are very difficult to quantify, with time horizons being much longer than those of the risk models. In the case of policy risk, the problem is the unpredictability of the political outcomes and lack of international cooperation, and I think this is one factor that really paralyses efforts in this area.

Physical risk requires dealing with a chaotic, random system where it’s very difficult to predict where and when disaster will strike. But we know there will be costs and exposures. Potential exposures and costs of natural disasters are rising so fast that it’s increasingly difficult to obtain insurance at an affordable price and, in some cases, insurance is not available at any cost.

Insurance risk really stands at the interface between physical risk and policy risk. As insurance firms raise premiums or withdraw from certain places, there needs to be a policy response. Governments need to step in to fill the vacuum.

Vince Kaminski

Trained in mathematics and economics, Kaminski has held teaching posts around the world including in his native Poland, Nigeria, the US and New Zealand. He has also been a Visiting Scholar at the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission in Washington, DC.

After working in bond portfolio analysis at Salomon Brothers between 1986 and 1992, Kaminski was headhunted by Enron where he worked for a decade leading a team of 50 quantitative specialists modelling exotic options and hedging commodity and interest rate exposures. Much of the risk management and valuation work carried out by his team during that time was pioneering.

Following his tumultuous final years at Enron – he was tied in by a contract until the bitter end in 2002 – Kaminski continued his career at hedge fund Citadel Investment Group before moving to Sempra Energy, Reliant Energy and Citigroup.

Now semi-retired, he teaches an extremely popular course on energy risk management at Jesse H Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University in Texas.

What are the biggest risks of the energy transition?

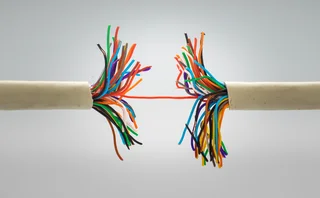

The biggest risk is that the energy system, a complex of global, integrated markets, will evolve faster than our ability to understand and manage it (not that we did a very good job in the past). I fear we could go down the route of making a complicated system more complex through micromanagement, new laws and regulations, tinkering with parts of the system without recognising the impact on other components of the system.

There are more specific risks, too. One is related to the integration of renewable energy sources within the pre-existing system. Some of my friends lost jobs because they failed to anticipate the consequences of the famous California duck (see graph) in power purchase agreements. As large amounts of solar power came onto the grid, intra-day prices dropped significantly during the day, creating the shape of a duck on a graph. Utilities or power marketers that had bought electricity at elevated prices found it couldn’t be resold during the day to cover the cost of power supply.

The second challenge is the pressure to recognise climate risk in risk assessment and management models. This pressure is coming from all directions, including regulators, creditors and credit rating agencies. The challenge is that the existing risk assessments are extremely myopic, dealing with the impacts of short-term, sometimes overnight, vibrations of prices. However, climate risks will unfold over decades. Assessing it is even harder than the early days of applying quantitative risk management to electricity markets. For climate risk we don’t have the benefits of the theoretical solutions that were developed in the 40 or so years running up to the 1990s.

When you look at energy crises like Storm Uri in 2021, how much do you think could have been averted and how much was beyond anyone’s control?

I think there is a common denominator to many fiascos I have seen in my career and it’s a conviction that the market will evolve in the desired direction or remain as is (depending on which side of the transaction we are on).

Another common problem is disregard of the complexity of the energy system and feedback loops between different parts of the system. The windstorm in Texas in 2021 is one example. The Ercot [Electric Reliability Council of Texas] electricity market is based on the principle of scarcity. This means there are no capacity markets (the payment for being available to produce) and electricity prices can increase to a very high level from time to time to cover fixed costs and accumulate funds for investments in generation and transmission. In February 2021, power prices rose to the highest legal maximum of $9,000 per megawatt hour. The freezing temperatures shut down a lot of natural gas infrastructure, limiting supplies and leaving electricity producers bidding up gas prices still further. The market had allocated limited gas supplies to the most efficient generators or the generators prepared for this emergency. As natural gas prices spiked, some local distribution companies paid more for natural gas in a week than they would usually pay in a year. So, both markets came under stress due to extreme, but perfectly predictable, weather events. This was a failure of imagination and a consequence of narrow specialisation. A competent risk manager has to understand not just an isolated, niche market but also the entire integrated system.

However, in reality, sometimes just the sheer weight of daily activities and fighting small fires like problems with posting collateral, reconciling transaction valuations, computer problems, can overwhelm risk teams and leave no time for brainstorming or identifying upcoming problems. I think one solution is to create a very diverse team of risk managers with many different skills. It’s necessary to allocate some time to thinking about the future.

I would be against early involvement of risk management in structuring transactions and in the decision-making process

Vince Kaminski

Do you think enough progress has been made in how risk management is viewed within energy organisations? Is risk involved in decisions early enough?

I have to give the benefit of the doubt to energy company executives; I haven’t heard anyone claiming that risk management is a waste of time, and I can only read their lips, not their brains. The answer to your question may surprise you but I would be against early involvement of risk management in structuring transactions and in the decision-making process. Based on my experience, early involvement is typically limited to inquiries about some aspects of a deal. At the point that risk managers are shown the entire transaction for assessment, they may see hidden risks and voice concerns. This can make for quite an angry reaction: “What is your problem? You were part of the process from the beginning and now you complain.” My recommendation would be to use an approach tried by some companies, including Citigroup, which have two risk groups. The ‘in-business’ risk group helps to identify and mitigate the risks of a transaction as it is being designed and negotiated. The independent risk group evaluates the final version of the transaction and, of course, may recommend going back to the drawing board.

Another good idea could be to combine the risk management team – which typically concentrates on the management of trading positions and hedging – with the strategy group that looks at risks such as those related to evolving market structure. Given how quickly markets are evolving today, there would be benefits to having one team look at both short-term price risk and longer-term risks arising from structural market changes driven by issues like climate policy, technological advancement or geopolitics.

Finally, to be fully effective, risk managers need to be independent of the C-suite and report directly to the board.

How do you prove the value-add of risk management and get a bigger budget?

Proving the value of risk management is extremely difficult, it’s almost as impossible as proving the negative. A failure of risk management is obvious; the successes remain hidden. Success has many fathers; a disaster is an orphan. When I teach risk management, I give many examples of well-documented fiascos and point out the basic principles of good risk management that were violated. It is indirect, circumstantial proof of the contribution of risk management to the bottom line. Having the best doctor does not guarantee that one does not get sick. But this is the best we can do.

Being a risk officer is a very difficult job. It’s like being a food taster in an old royal court: limited upside, inability to stop a slow-acting poison and the cooks don’t like you

It takes considerable power of persuasion to convince senior management about the value of the risk management unit and the need for continuous funding. Senior management often has a tendency to ‘tick the box’, conclude that the problem was solved and redirect the funds to other uses.

When evaluating a risk management function, it’s worth remembering it’s only as good as the processes around it. The system might look great on paper, but if, in reality, transactions are sometimes (as I know from experience) passed to the risk department on Friday evening for a deal that management signs off on Monday morning, risk cannot do a good job. They are effectively circumvented.

What’s been the biggest breakthrough in quantitative energy risk analysis that you’ve seen during your career? Where does progress still need to be made?

I think the biggest breakthrough happened in the 1990s when energy companies invested in the infrastructure of risk management. We made collectively more progress in risk management in the 1990s than in the last 25 years. The existing solutions have many flaws, but they are better than nothing. As we know, all models are wrong, but some are useful. What is important is to understand the limitations of the existing tools.

Unfortunately, once the infrastructure of risk management was in place, the problem was considered solved and there was a false sense of security. One concern I have is that many energy risk management systems in big companies remind me of the Winchester Mystery House, [a mansion in San Jose, California owned in the late 1890s to early 1900s by Sarah Winchester, the widow of a firearms magnate]. The house is renowned for its extraordinary and ad hoc extensions, which resulted in a chaotic design with stairs leading nowhere, disconnected additions, doors opening to brick walls and walled-off exterior windows.

Many energy risk management systems in big companies are similar, consisting of numerous different components based on different assumptions and technologies, applications that don’t interact well and are connecting by excel spreadsheets, which are a very unstable way of communicating between software systems.

I think a significant research effort is needed to improve the analytical tools used in energy risk management, especially given the proliferation of renewables, which are changing price dynamics and leading to, for example, negative electricity prices.

We made collectively more progress in risk management in the 1990s than in the last 25 years

What specific industry problem would you most like to see quantitative energy risk management tackle next, and do you believe it could ever be solved?

I think the most urgent task is to develop models that better describe interactions between renewable and conventional sources of electricity. There are good reasons to believe that the recent electricity outage in Spain and Portugal happened when the grid had a very low inertia – a low percentage of gas-fired generation – and was aggravated by technicalities related to how direct current produced by solar and wind is converted into alternating current.

We also need better tools for simulating energy prices with unique characteristics such as jumps, seasonality, potential negativity and intraday patterns.

In what ways might technology and AI augment quantitative risk management and analysis in the coming years?

I would not trust AI-generated solutions blindly, given their propensity to hallucinate. It can be very useful in automating certain labour-intensive, mundane tasks, such as data collection and cleaning, and identification of patterns in the data, but only under adult supervision. Ironically, in the long run AI may have negative impacts on many companies by eliminating many entry-level jobs and slowing down hiring. I have many signals from my students that this is going on. We have a very difficult labour market for recent graduates in the US. I fear that this is comparable to cutting off or reducing oxygen flow to the body. It is a very myopic policy.

What are the most important character traits of a senior risk officer?

Being a risk officer is a very difficult job. It’s like being a food taster in an old royal court: limited upside, inability to stop a slow-acting poison and the cooks don’t like you. A risk officer has to know the minutiae of many markets whereas a potential rogue trader has the benefit of specialisation. The most important trait is the ability to learn, absorb and process information. In other words, a risk officer must be a jack of all trades. In terms of personality, a successful risk officer must combine traits seldom found together in one person – an amiable, likeable, cordial person with a spine of steel.

Most risk officers are used to having uncomfortable conversations from time to time, but how did you feel when you realised the full extent of the problems at Enron?

This was a difficult moment in my life. I became very uncomfortable with the initiative of Enron’s chief financial officer to create off-balance sheet platforms to hedge Enron’s risk – the vehicles that he would manage. This was an obvious conflict of interest, and it cost Enron the confidence of the market – and a trading shop cannot afford a loss of confidence. I anticipated the potential problems, and the risk assessment produced by my group confirmed my fears. I was ready to fall on my sword and told my boss that I was willing to explain to the board of directors why I think the CFO’s idea is a very bad one. People like me don’t usually interact with the board. I suffer from uncontrollable urges to tell the truth. My boss said he would be more qualified (or diplomatic) to do it, but later told me that he could not stop the project. I think at this point the fate of Enron was sealed. For the rest of my career at Enron I was marginalised and isolated. I could not leave because of the employment contract; Enron could not fire me because it would send a very bad signal to the market. So, we had a stalemate.

Would you do anything differently if you had your career over again?

I would better manage the learning process, especially the process of identifying new things that need to be mastered to be effective. There are limits to how much one person can really learn in depth. One should decide what really matters and concentrate on these things. I think I learned over time how to prioritise and how to delegate.

What has surprised you most about working in energy risk management?

I was surprised many times by the desire to please one’s superiors, even if it creates potential exposures and risks to the pleasers. People like to be patted on the back. That makes them vulnerable to manipulation and if they have the bad luck to be in a criminogenic environment, that may lead to real problems.

People like to be patted on the back. That makes them vulnerable to manipulation and if they have the bad luck to be in a criminogenic environment, that may lead to real problems

What advice would you give to people starting out in the field of energy risk management today?

My advice would be read, study and learn as much as you can and avoid narrow specialisation. Understand all three different layers of the energy markets: physical; financial; and wider fundamentals, such as geopolitics and policy. It’s important to understand physical operations, the characteristics of different assets, production, storage and transportation so you understand when constraints may develop in the physical system. Then you need a full understanding of financial and spot transactions in different markets, understanding the different types of transactions, who the market participants are, how prices are formed and the interactions between markets. And finally, you need to understand and follow laws, regulations, international conventions, geopolitical issues and so on. I emphasise to students you need to understand all three layers to understand the interactions and feedback loops between different parts of the system and how shocks are transmitted through the system. It’s evolving all the time so the solution is to have an open mind, read and study widely, even things that on the surface don’t seem related to the energy markets but sooner or later they may affect them.

The advice I’ve given to many quantitative analysts working in my group is don’t spend too much time making tiny adjustments to models in the pursuit of perfection. While improving the measurement of the height of a molehill you can miss the mountain. In the grand scheme of things, small improvements often don’t matter that much – what matters is what’s lurking behind the horizon. Even the best model is not a substitute for experience and understanding of the markets.

More on Risk management

Energy firms revisit CTRM systems as tech advances

Energy executives mull how to tap into the explosion of new technologies entering the risk space, but systems selection must consider future business needs, writes Yefreed Ditta at Value Creed

CRO interview: Brett Humphreys

Brett Humphreys is head of risk management at environmental markets specialist Karbone. He talks to Energy Risk about the challenges of modelling outcomes in unpredictable times and how he’s approaching the risks at the top of his risk register

How geopolitical risk turned into a systemic stress test

Conflict over resources is reshaping markets in a way that goes beyond occasional risk premia

Energy Risk Debates: the influence of risk culture

The panellists examine different risk cultures and discuss the risk manager’s role and influence in creating a risk culture

Energy Risk reaction: Venezuela and oil sanctions

Energy Risk talks to Rob McLeod at Hartree Partners about the energy risk implications of the US’s control of Venezuelan oil

CRO interview: Shawnie McBride

NRG’s chief risk officer Shawnie McBride discusses the challenges of increasingly interconnected risks, fostering a risk culture and her most useful working habits

Increasingly interconnected risks require unified risk management

Operational risk is on the rise according to a Moody's survey, making unified risk management vital, say Sapna Amlani and Stephen Golliker

Energy Risk Europe Leaders’ Network: geopolitical risk

Energy Risk’s European Leaders’ Network had its first meeting in November to discuss the risks posed to energy firms by recent geopolitical developments